Representations of spatial location by aperiodic and alpha oscillatory activity in working memory

Update (July 2025): We recently published this work in PNAS!

Background: Working memory (WM) refers to one’s ability to hold and manipulate a limited amount of information in mind for a short period of time, usually on the order of seconds, and is integral to many other cognitive functions. Previous work from Foster and colleagues (2016) demonstrated that the topography of alpha-band activity (8–12 Hz) tracks the spatial location in stimuli in WM, suggesting that alpha oscillations coordinate the cellular assemblies that code the content of WM. Previous work in our lab by Donoghue, Haller, Peterson, et al., (2020) has shown that standard spectral analyses can conflate oscillatory changes with change in aperiodic activity. In this project, we sought to distinguish the roles of alpha oscillatory and aperiodic activity in WM using sliding-window spectral parameterization to ensure the development of an accurate physiological understanding of visual WM and the true role of alpha oscillations therein.

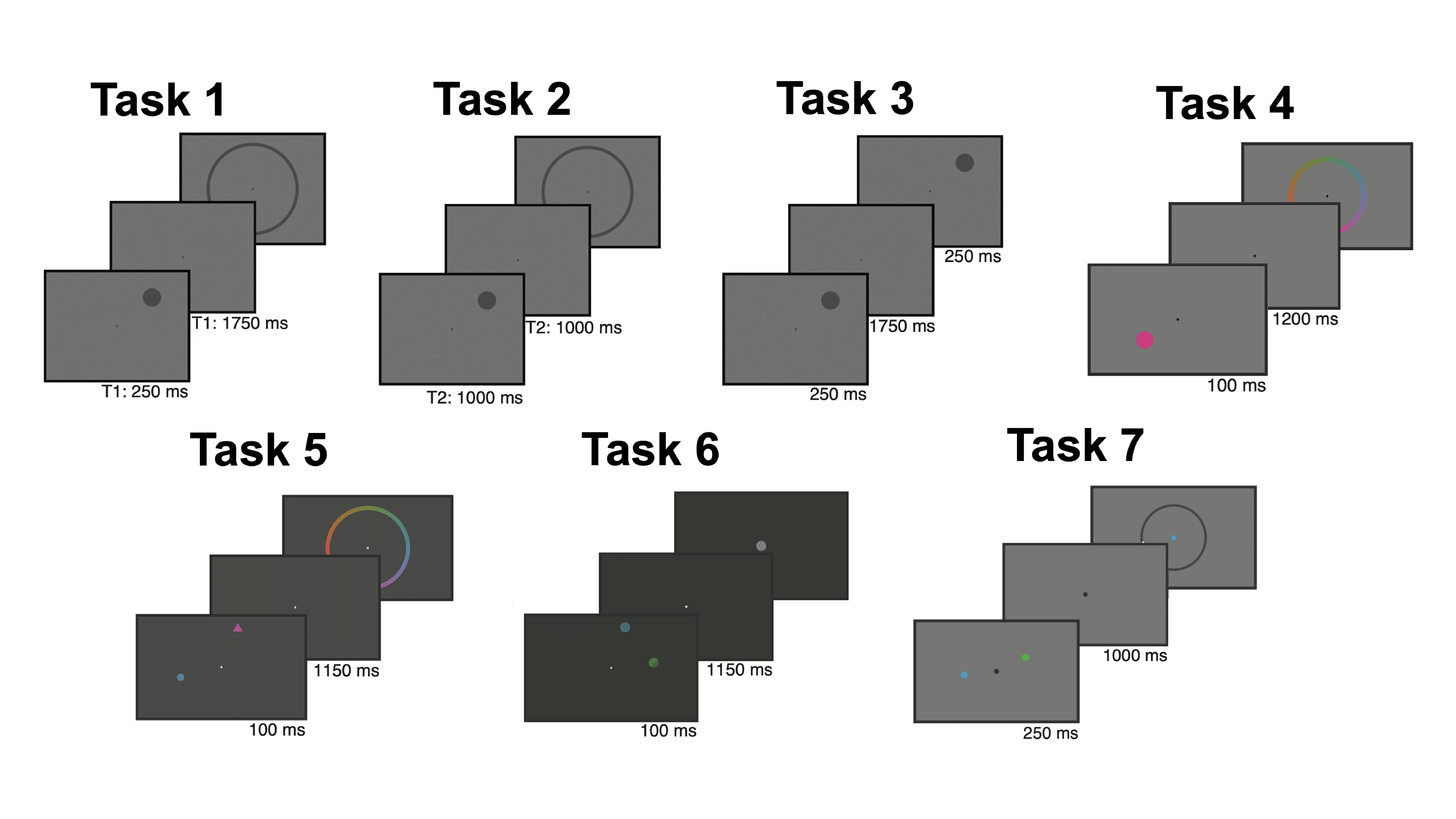

Methods: In collaboration with Drs. Ed Awh and Ed Vogel, we used EEG data from participants at the University of Oregon (n = 56) and the University of Chicago (n = 56) that came from three published, publicly available datasets (Foster et al., 2016; Foster et al., 2017; Sutterer et al., 2019). Even though the EEG data come from seven different tasks, all data were collected while participants attended and remembered features of stimuli presented around fixation across a delay, requiring WM. All tasks were continuous report, where participants were required to report the location, color, or orientation of the target stimulus, except for task 3, where participants only had to indicate whether there was a change in the probe stimulus from the target stimulus:

We computed spectrograms for each sensor and determined the aperiodic exponent and alpha oscillatory power for each time point using spectral parameterization. Following the procedure of the Foster and colleagues (2016), we then fit an inverted encoding model (IEM) to assess how strongly spatial location was represented by the aperiodic exponent and alpha oscillatory power throughout the trial.

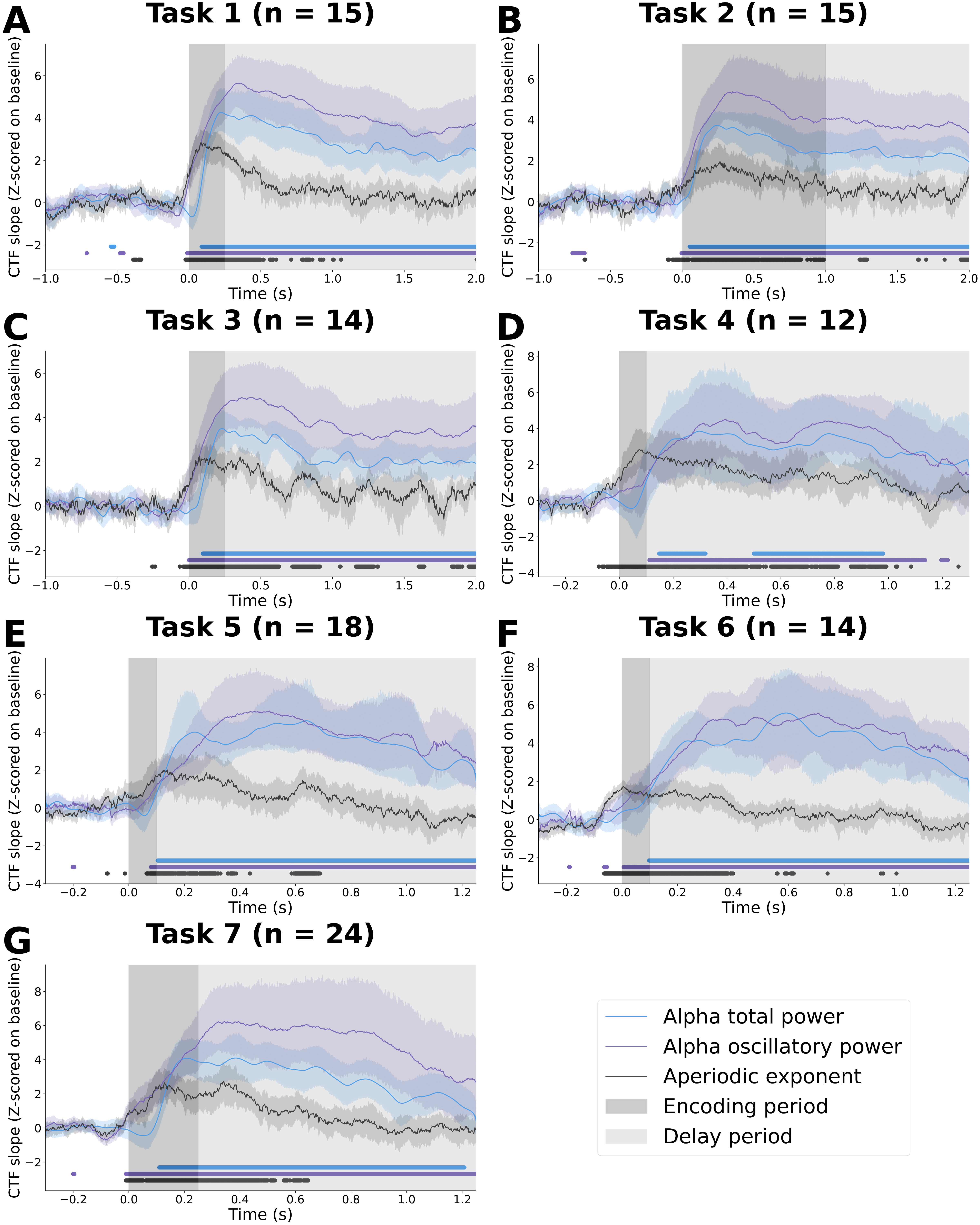

Results: We first reproduced the authors’ findings that total alpha power represents spatial location during WM. The channel tuning function (CTF) slope, which assesses how strongly the population activity in the alpha band represents the spatial location of the stimulus, increases soon after stimulus presentation and remains high throughout the delay period (blue line for each task below):

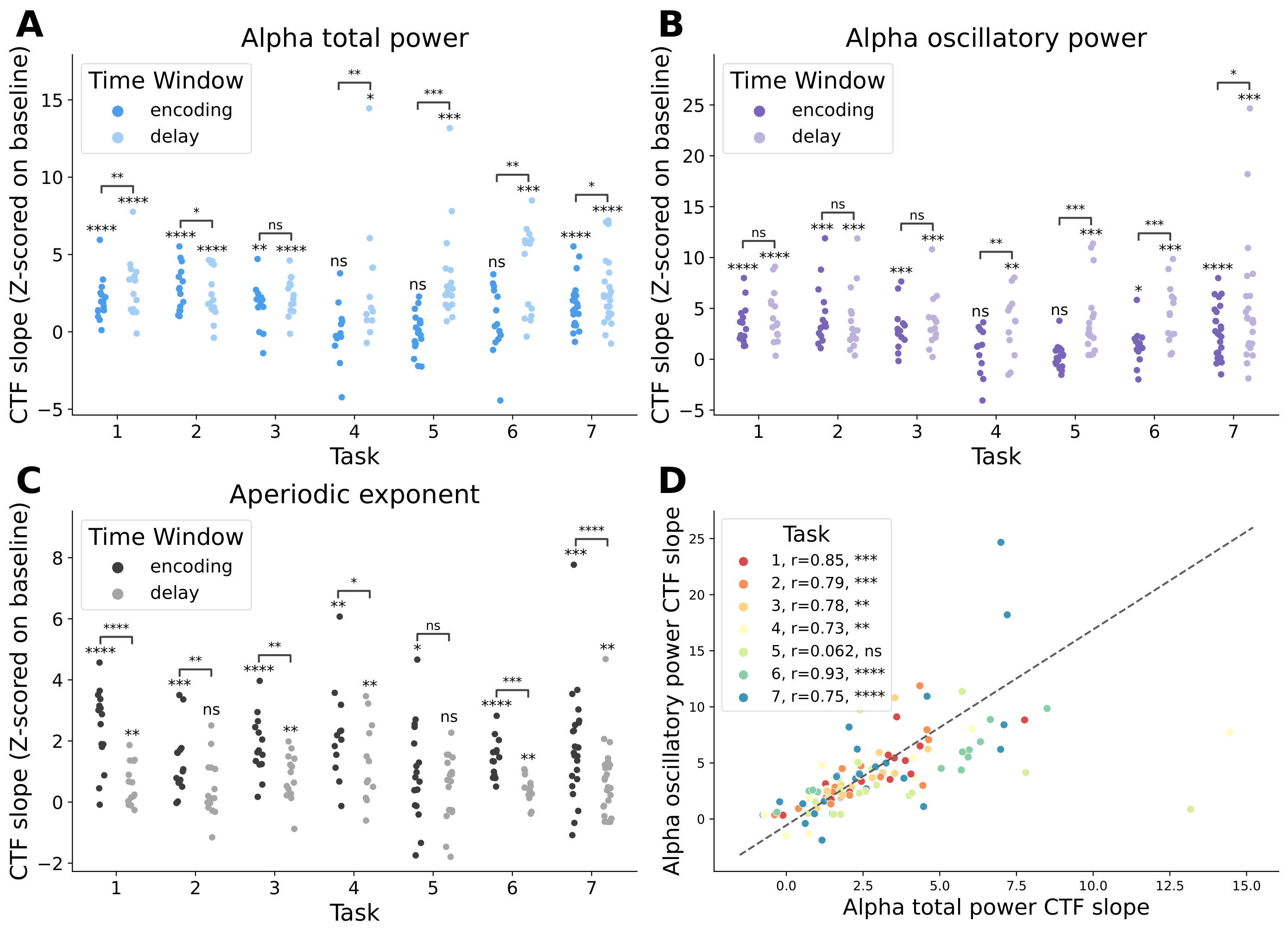

There is strong representation of spatial location by alpha oscillatory power throughout the delay period (purple line for each task above) in each of the seven tasks, supporting the idea that alpha oscillations act as a scaffolding signal that coordinate which of the underlying retinotopic cellular assemblies maintain the stimulus features in working memory. This representation of spatial location by alpha oscillatory power was significantly greater across the delay period than when location labels were shuffled (light purple in B below):

By contrast, representation of spatial location by the aperiodic exponent peaks during the early portion of the stimulus presentation for all seven tasks (black line in CTF time courses for each task). Moreover, this early peak in aperiodic activity representation of spatial location occurs soon after stimulus onset regardless of the total stimulus presentation time, suggesting that aperiodic activity encodes spatial location quickly and automatically once the stimulus has been presented. This representation is consistent with previous work in our lab by Gao et al., (2017) that showed that the aperiodic exponent reflects the relative balance of excitation and inhibition in the underlying neural populations, such that a surge of excitation in the underlying neural populations necessary to encode the stimulus features during stimulus presentation is reflected in detectable changes in the EEG aperiodic exponent. The representation of spatial location by the aperiodic exponent was significantly greater in the encoding period than when location labels were shuffled (dark black in C above).

Conclusion: We confirmed previous findings that the topography of alpha oscillatory activity represents spatial location in working memory, deconfounding these effects from changes in aperiodic activity. Furthermore, we discovered that the aperiodic exponent represents spatial location during the first 400 ms after stimulus presentation. Together, these findings highlight the utility of sliding-window spectral parameterization to decouple and characterize two, time-varying, physiologically distinct neural mechanisms for encoding and working memory.

- Manuscript

- A. Bender, C. Zhao, E. Awh, E. Vogel, B. Voytek. (2025). Differential representations of spatial location by aperiodic and alpha oscillatory activity in working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(30), e2506418122. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2506418122.

- Presentations

- A. Bender, B. Voytek. Representations of spatial location by aperiodic and alpha oscillatory activity in working memory. Cognitive Neuroscience Society; 2024, April 14; Toronto, ON. (poster)

- A. Bender,, B. Voytek, Decoding spatial location from aperiodic and alpha oscillatory activity in working memory. Society for Neuroscience; 2023, November 13; San Diego, CA. (presentation)

Developmental changes in alpha and mu rhythms

Update (June 2025): We recently published this work in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience!

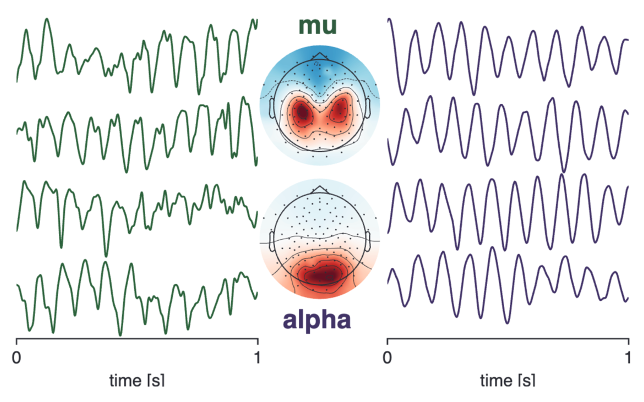

Background: Alpha rhythms in occipital cortex and mu rhythms in sensorimotor cortex are two of the most prominent rhythms in the human brain (example rhythms and corresponding spatial topographies are shown to the right). They have similar characteristic frequencies in the canonical alpha band (8–12 Hz) and serve important functions in gating modality-specific information. Both alpha-band rhythms have been implicated in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in disorder-relevant tasks (e.g., social encoding tasks for ASD and attention-demanding tasks for ADHD). In this project, we investigated whether these rhythms could serve as biomarkers for these developmental disorders in resting-state electroencephalography (EEG). Such biomarkers would greatly aid in developing effective early diagnostic tools for ASD and ADHD.

Background: Alpha rhythms in occipital cortex and mu rhythms in sensorimotor cortex are two of the most prominent rhythms in the human brain (example rhythms and corresponding spatial topographies are shown to the right). They have similar characteristic frequencies in the canonical alpha band (8–12 Hz) and serve important functions in gating modality-specific information. Both alpha-band rhythms have been implicated in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in disorder-relevant tasks (e.g., social encoding tasks for ASD and attention-demanding tasks for ADHD). In this project, we investigated whether these rhythms could serve as biomarkers for these developmental disorders in resting-state electroencephalography (EEG). Such biomarkers would greatly aid in developing effective early diagnostic tools for ASD and ADHD.

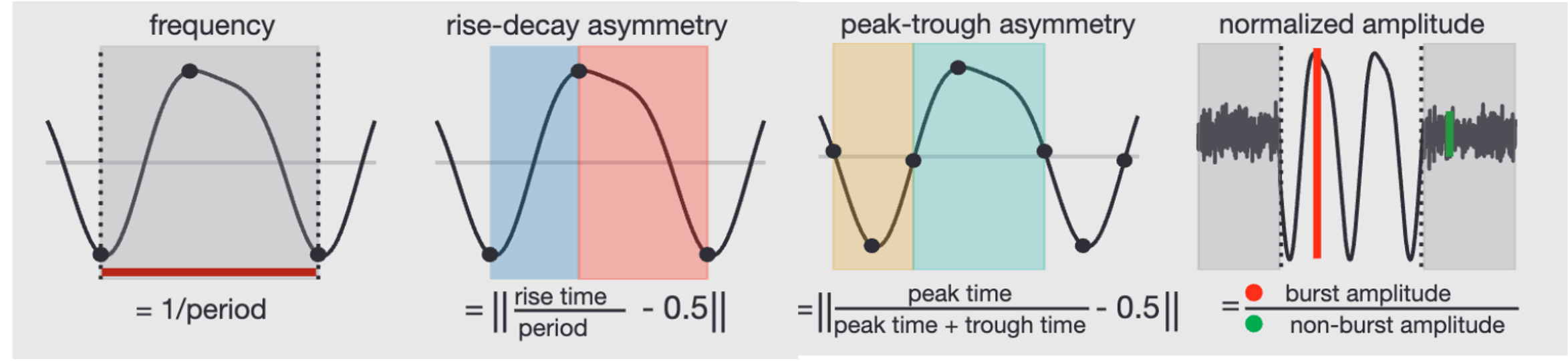

Methods: We used an openly available developmental dataset of resting-state EEG recordings from nearly 3000 children (ages 5–18) from the Child Mind Institute published by Alexander and colleagues (2017). We isolated high-fidelity alpha and mu rhythms from these recordings using an computationally efficient integration of spectral parameterization, spatial filters, and source localization. We then used burst detection and waveform shape analysis to characterize the time series of these isolated alpha and mu rhythms:

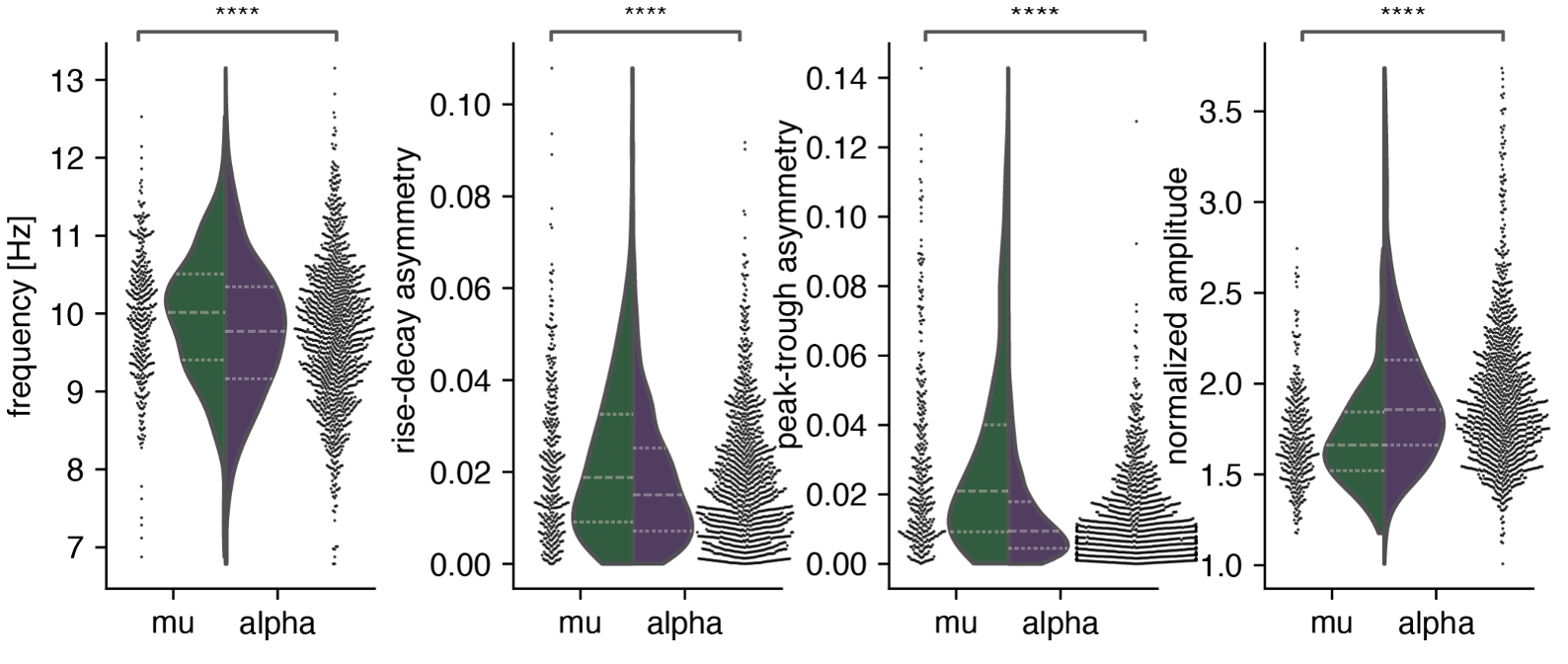

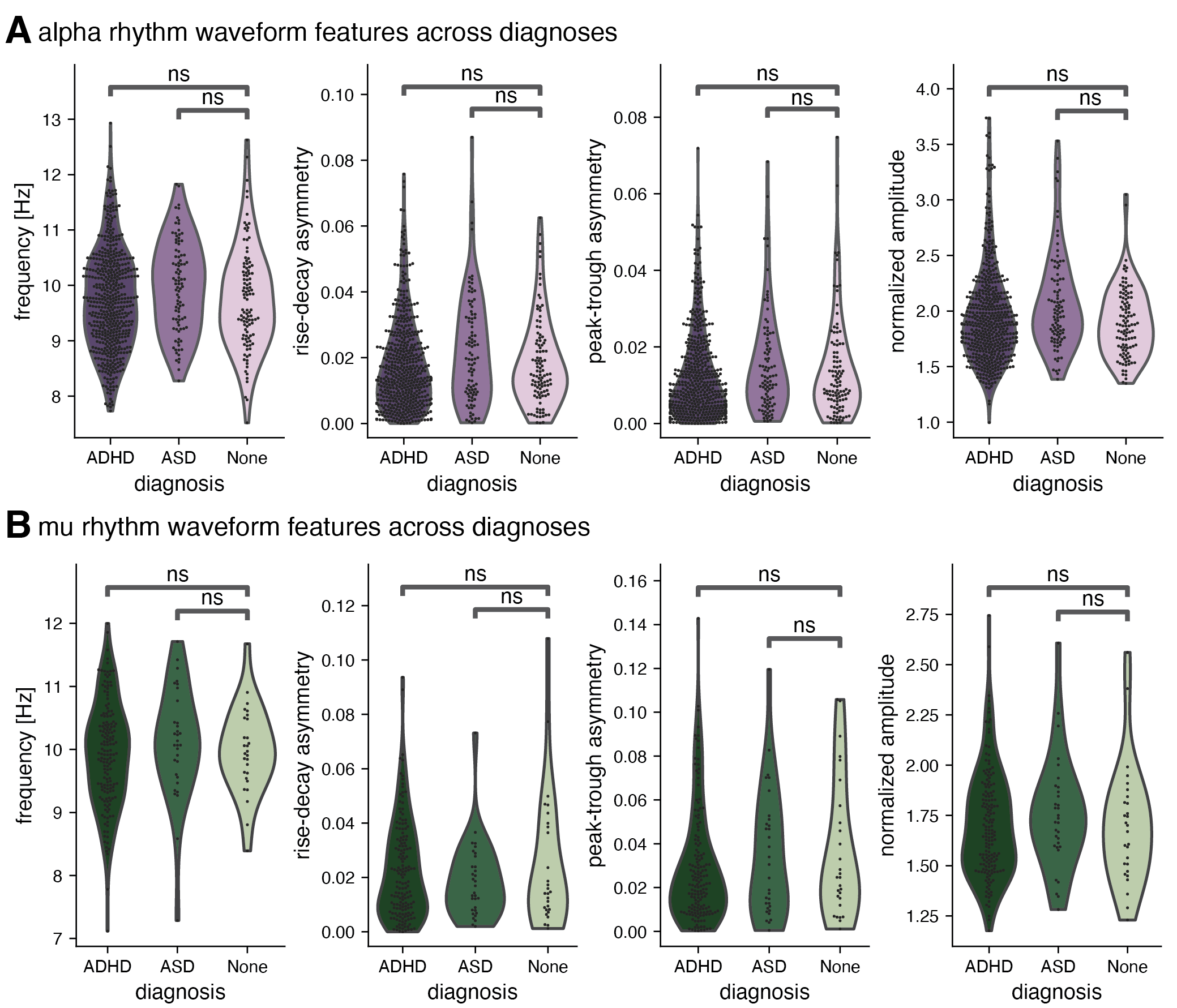

Results: First, we demonstrated that alpha rhythms are lower frequency, less asymmetrical, and higher amplitude than mu rhythms. These results quantifiably replicate qualitative differences in alpha and mu at an unprecedented scale:

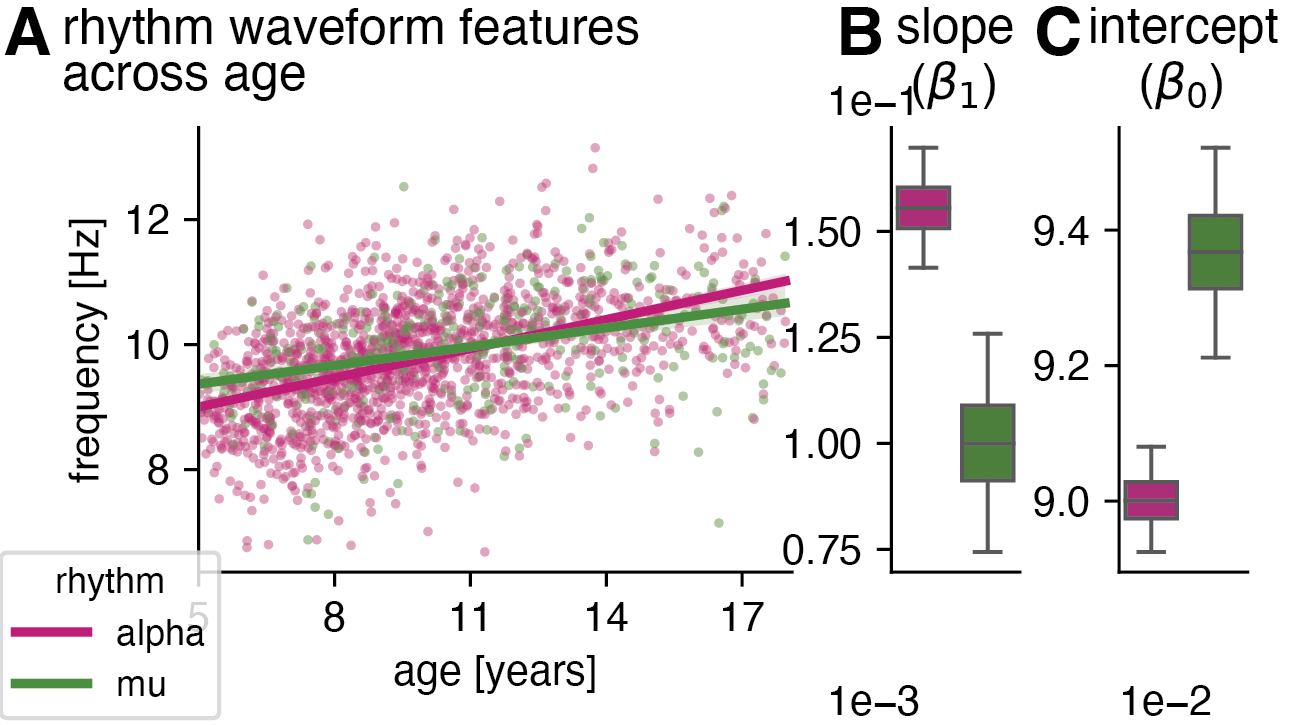

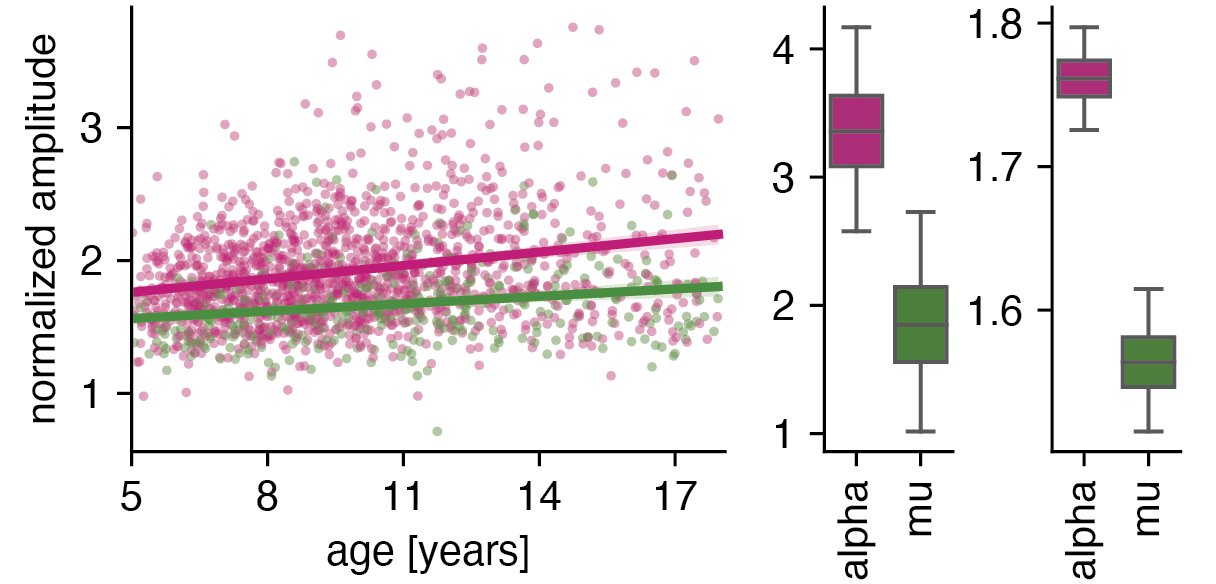

Next, we discovered that alpha and mu rhythms are significantly different at age five and change differently across development:

Finally, we showed that neither alpha nor mu rhythms are sensitive biomarkers in resting-state EEG, implying sensitive EEG biomarkers for ASD and ADHD may require deficit-specific task operationalization:

Conclusion: We extended previous findings of alpha-band rhythms undergoing large changes in frequency during development, showing that these waveform shape measures also change substantially across development. While none of these resting-state changes appear to be associated with common neurodevelopmental disorders, characterizing differences across rhythm types remains vital for constraining generative models for alpha-band rhythms.

- Manuscript

- A. Bender, B. Voytek*, N. Schaworonkow*. (2025). Resting-state alpha and mu rhythms change shape across development but lack diagnostic sensitivity for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism. J Cogn Neurosci. 37(9), 1581–1615. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_02323. *These authors contributed equally to this work.

- Presentations

- A. Bender, B. Voytek, N. Schaworonkow. Age-related changes in alpha and mu oscillation amplitude and waveform asymmetry. Society for Neuroscience; 2022, November 16; San Diego, CA. (poster)

- A. Bender, B. Voytek, N. Schaworonkow. Quantifying waveform shape of EEG alpha and mu oscillations across development. Cognitive Neuroscience Society; 2022, April 26; San Francisco, CA. (poster)

- A. Bender, B. Voytek, N. Schaworonkow. Quantifying waveform shape of EEG alpha and mu oscillations across development. Society for Neuroscience; 2021, November 9; remote. (presentation)

Classification of autism spectrum disorder from structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging using machine learning

Background: Machine learning and deep neural networks have shown promise in helping to diagnose diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease from neuroimaging datasets. Given the utility machine learning has already shown in diagnosing diseases, here we aimed to develop machine learning classifiers, including a deep residual neural network called ASDNet, that can classify autism spectrum disorder (ASD) from neuroimaging data. Because early diagnosis and early treatment can improve quality of life for individuals with ASD and their families and current diagnostic measures can only be used with children 12 months and older, machine learning shows promise for enabling earlier diagnosis and treatment of ASD.

Methods: We used the following publicly available preprocessed data from the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) (Di Martino et al., 2014): (1) T1-weighted structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI), (2) 3D volumes of voxel-wise cortical thickness, and (3) mean functional activation volumes from 531 individuals with ASD and 570 typically developing individuals.

Methods: We used the following publicly available preprocessed data from the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) (Di Martino et al., 2014): (1) T1-weighted structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI), (2) 3D volumes of voxel-wise cortical thickness, and (3) mean functional activation volumes from 531 individuals with ASD and 570 typically developing individuals.

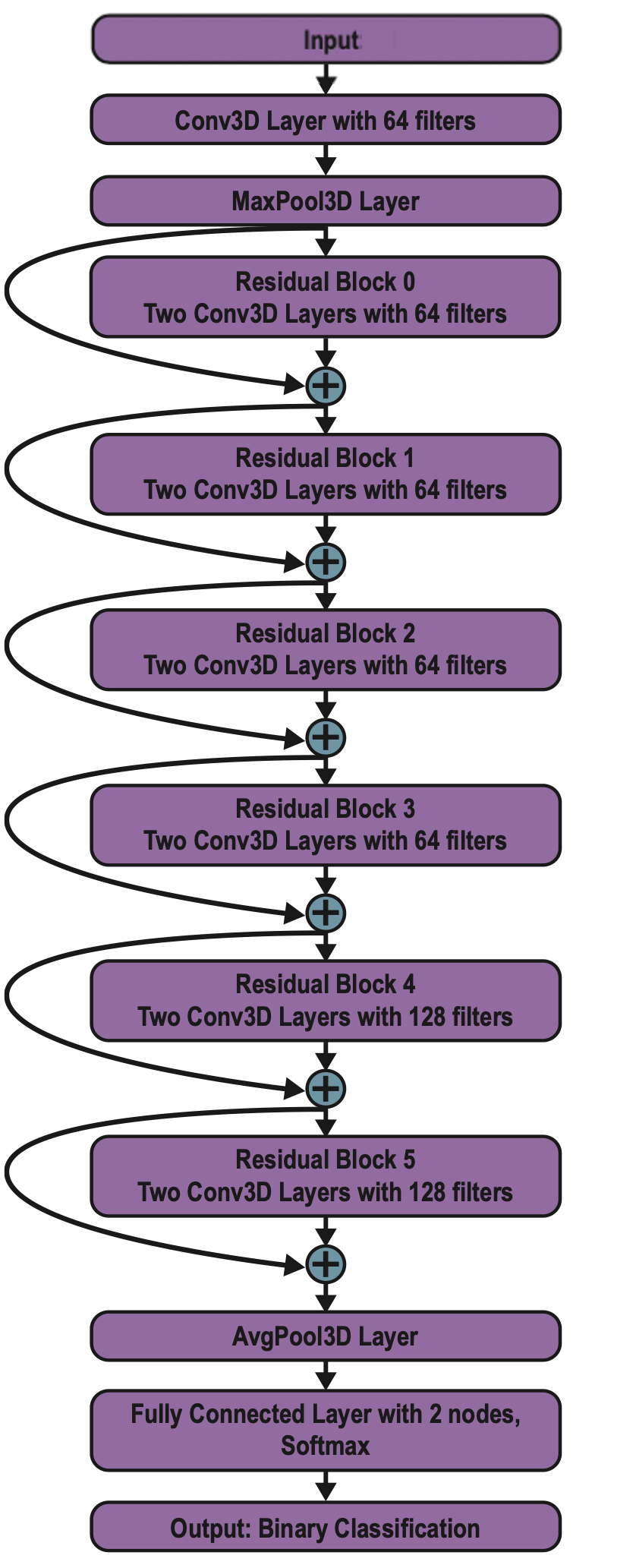

We created nearest neighbor, Naïve Bayes, and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) classifiers to diagnose ASD on the first 1100 principal components for each individual imaging modality (structural, cortical thickness, and functional). We also trained classifiers for each combination of imaging modalities (e.g., structural + functional). We used 8-fold cross-validation to validate classifier performance. In addition, we trained a custom-built GPU implementation of a deep 3D residual neural network in TensorFlow to perform the classification, following a similar architecture to a network used to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease from neuroimaging data (Yang et al., 2018). The complete architecture of ASDNet is shown to the right.

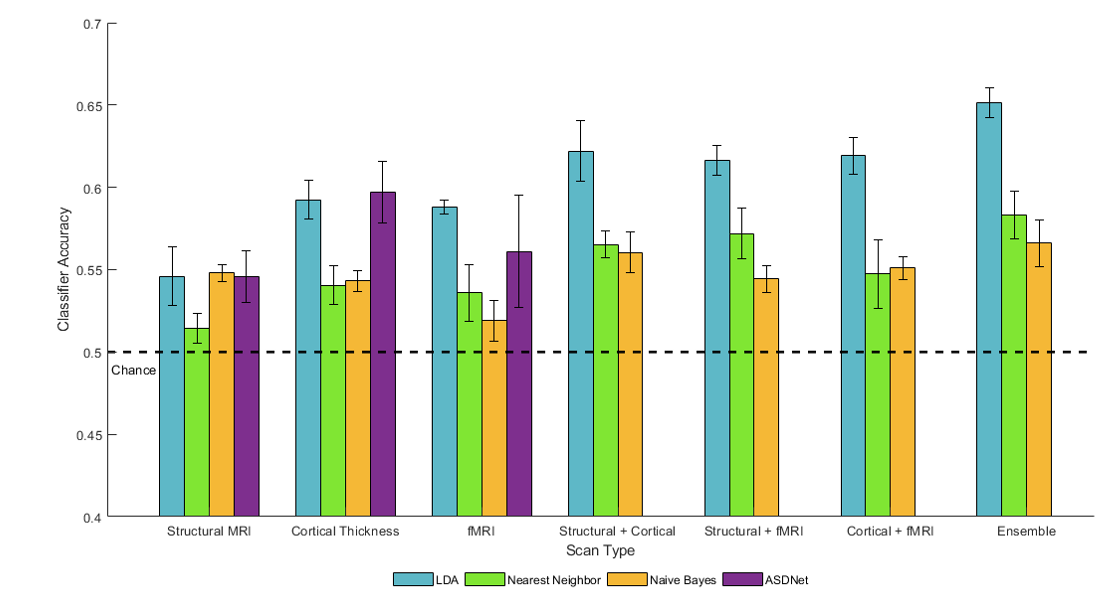

Results: The classification accuracy for each classifier on the structural, cortical thickness, and function volumes is shown below:

LDA had the best average classification accuracy across the three types of imaging out of the four classification methods, with ASDNet classifying structural and cortical thickness volumes with similar accuracy and performing worse on the functional volumes than LDA. Putting data from two imaging types together into an ensemble increased classification accuracy with all three classifiers it was attempted with (LDA, Naïve-Bayes, and nearest neighbors). The ensemble containing all three imaging types performed the best. Finally, use of cortical thickness volumes and functional volumes led to higher classification than use of structural MRI, although the pairwise combinations of imaging types as an ensemble led to similar classification accuracies for all three pairwise combinations.

We further showed through distance to bound analysis that structural, cortical thickness, and functional differences extracted by classifiers were significantly correlated to Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (Lord et al., 2000) scores, a common behavioral assessment for ASD that is considered to have state-of-the-art sensitivity (Randall et al., 2018).

Conclusion: The classification achieved was significantly above chance, but far below that which would be required for any utility in early diagnostics of ASD. There are a variety of possible causes—relatively raw neuroimaging data, limited training data (~1000 subjects of high-dimensional data is nothing compared to the training sets used on most deep ANNs), insufficient hyperparameter tuning—to name a few, and I would have approached this problem differently had I continued this research in graduate school. Nonetheless, I cultivated many technical skills that have benefitted my graduate career immensely and machine learning still shows great potential as an early diagnostic tool to reduce the financial, psychosocial, and developmental burden of ASD on our society despite our inability to demonstrate so with this particular work.

- Honors Thesis (Awarded Highest Honors in Neuroscience)

- A. Bender, D.A. Tovar, M.T. Wallace. Classification of Autism Spectrum Disorder Using Machine Learning. Honors Thesis Defense; 2019, April 18; Nashville, TN. (paper, presentation)

- Presentations

- A. Bender, D.A. Tovar, R. Ramachandran, M.T. Wallace. ASDNet: Classification of autism from MRI images using residual neural networks. Vanderbilt Translational Research Forum; 2018, October 26; Nashville, TN. (poster)

- A. Bender, D.A. Tovar, R. Ramachandran, M.T. Wallace. ASDNet: Classification of autism from MRI images using residual neural networks. Summer Student Poster Presentations: Vanderbilt Undergraduate Research Fair; 2018, September 27; Nashville, TN. (poster)